Derviş, Κ. & Saraceno, F. (2014) “An Investment New Deal for Europe“, Brookings Blog, 03 Σεπτεμβρίου.

Six years into the crisis, the eurozone remains the sick man of the world economy. Its GDP today is barely at the pre-crisis level, deflation looms and the difference between the healthier core and a struggling periphery is not resolved. Moreover, even Germany may be slowing down, and Finland is in persistent recession.

By announcing the Outright Monetary Transactions (OTM) back in 2012, Mario Draghi defused the financial crisis by promising to act as a de facto lender of last resort for troubled southern economies. Then, last June, the European Central Bank (ECB) embarked on its own version of quantitative easing, promising credit to eurozone firms and households. The ECB has been blamed in some quarters for doing too little, too late. It is probably true that the deflationary threat had been underestimated by ECB officials. It should be recalled, nevertheless, that the ECB fought the crisis, facing resistance from some of its most influential members. It saved the eurozone from disintegration but it has not been able to help launch growth. On the contrary, it is increasingly evident today that the impact of monetary policy on growth is limited. Balance sheet recessions increase the propensity to hoard among households, firms and financial institutions. In a liquidity trap monetary policy loses traction. Today, stagnant income and high unemployment in most eurozone economies, and uncertainty about the future, all contribute to compress private spending and demand for credit across the eurozone, while they increase the appetite for liquidity. At the end of 2013, private spending was 7 percent lower than in 2008 (a figure that reaches a staggering 18 percent for peripheral countries). In such a situation there is only so much the ECB can do.

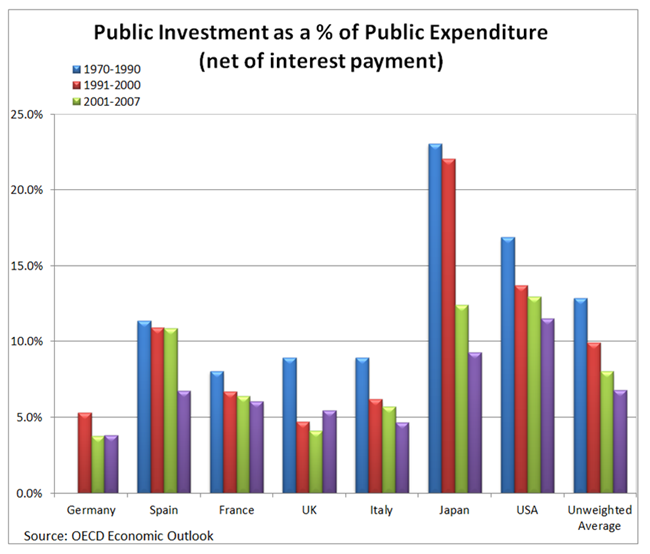

Monetary policy has been given almost obsessive attention, but there has been much less debate about the nature of fiscal policy. That may be changing, however, as Mario Draghi’s speech in Jackson Hole signals. True, the European Commission and Germany have insisted that fiscal consolidation should be strengthened further. Yet, the argument for boosting public investment seems to have gathered strength and is likely to be discussed at the next European Council meeting. This is long overdue: Since the Maastricht Treaty, cutting public investment has been the preferred instrument for fiscal consolidation by many countries, because it is generally less immediately painful than other cuts. The result is that in almost all eurozone countries public investment as a share of public spending decreased dramatically compared to the 1970s and 1980s.

Σχετικές αναρτήσεις:

- Szczurek, M. (2014) “Investing for Europe’s Future“, VoxEU Organisation, 05 Σεπτεμβρίου.

- Pisani-Ferry, J. (2014) “Can Investment Save Europe?“, Project Syndicate, 30 Ιουλίου.

- Papadimitriou, Β. D. & Toay, T. (2014) “Co-operative Banking in Greece: A Proposal for Rural Reinvestment and Urban Entrepreneurship“, Levy Economics Institute, Research Project Reports, Ιούλιος.