Niehues, J. (2014) “Cross-country differences in perceptions of inequality“, VoxEU Organisation, 28 September.

Income inequality is high in the US, but the support of social welfare programmes is low. In Europe, income inequality is low and the welfare states are generous. This column argues that this paradox is largely due to perceived inequality. Many Europeans believe that there is high inequality in their countries, justifying the need for redistributive policies. Americans, however, are less concerned with income differences and with respective redistributive state intervention.

The well-known and frequently tested median voter theorem predicts a positive relationship between income inequality and state redistribution; if the decisive median voter’s income is below the social average, he votes for more welfare redistribution because he expects to benefit from progressively financed welfare programmes. However, this theory does not perform very well when confronted with data. Although income inequality is high in the US, support for welfare state programmes is relatively low. In contrast, income differences in European countries are substantially lower. Still, the European welfare states tend to be far more generous. Obviously, there might be a row of other individual and national factors which may explain the US-European differences in redistributive preferences (Alesina et al. 2001). For example, Americans may just accept certain inequalities because they see them as a reward for effort and believe in the chance of upward mobility (‘American exceptionalism’). On the other hand, Europeans may view income positions rather as the result of luck and other exogenous circumstances and, therefore, demand more state redistribution. However, as the current research on mobility reveals, countries with higher inequality are also associated with less income mobility (e.g. Corak 2012).

Given this puzzling evidence, it is not surprising that economists have become increasingly interested in the importance of attitudinal data when explaining redistributive preferences. In this regard, in a study on the UK, Georgiadis and Manning (2012) find that beyond the standard political economy model, beliefs and attitudes are especially important explanatory factors of the individual demand for redistribution. Looking at perceived and desired pay differentials, they provide some evidence that inequality aversion is a relevant determinant — those who perceive more pay inequality are in favour of more redistribution. Inequality aversion with respect to pay differentials is very similar between Europe and the US (Osberg and Smeeding 2006), thus failing to explain ‘the paradox of redistribution’ between them. However, the concept of perceived pay inequality does not include any information about the respondent’s estimate of the frequency of each occupation in the population. It may well be the case that people underestimate the extent of pay inequality, while simultaneously overestimating the fraction of the population affected by it.

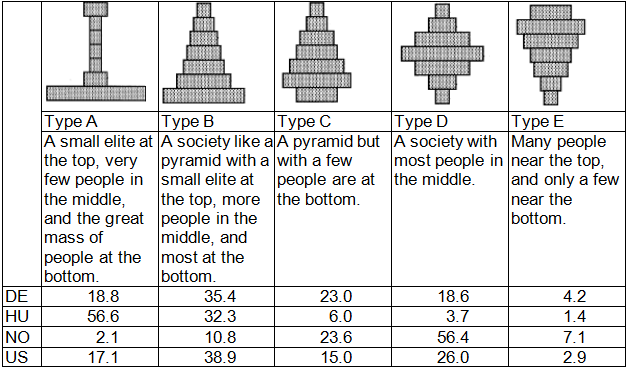

Table 1. Perceived types of society

Relevant posts:

- Esposito, M. & Tse, T. (2014) “Income Inequality and Youth Unemployment“, Project Syndicate, 25 June.

- Teulings, C. (2014) “Why does inequality grow? Can we do something about it?“, VoxEU Organisation, 15 June.

- Hoffer, F. (2014) “Inequality And Post-neoliberal Globalisation“, Social Europe Journal, 29 May.