Morris, I. (2015) “The Lunch Question – A Brief History of Inequality“, Global Affaris, STRATFOR Global Intelligence, 11 Φεβρουαρίου.

At an event in Beijing last November, I had the good fortune to meet the French economist Thomas Piketty, who has sold 1.5 million copies of his book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, since it was first published in 2013. Pacing up and down in front of a packed auditorium, Piketty explained that because the rate of return on capital is now higher than the growth rate of the global economy, the proportion of the world’s wealth that is owned by a small elite will likely keep increasing; in other words, we should expect to see a divergence of wealth as the rich get much richer. As his book says, “capitalism automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that radically undermine the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based.”

No strategic forecaster can afford to ignore this alarming prediction — or the enthusiastic response it got from the audience in Beijing. In the 20th century, the two world wars were the only force powerful enough to reverse the concentration of wealth in the elite and the mounting class conflict; in the 21st century, we seem to be falling back into a comparable world of revolution, political extremism and mass violence.

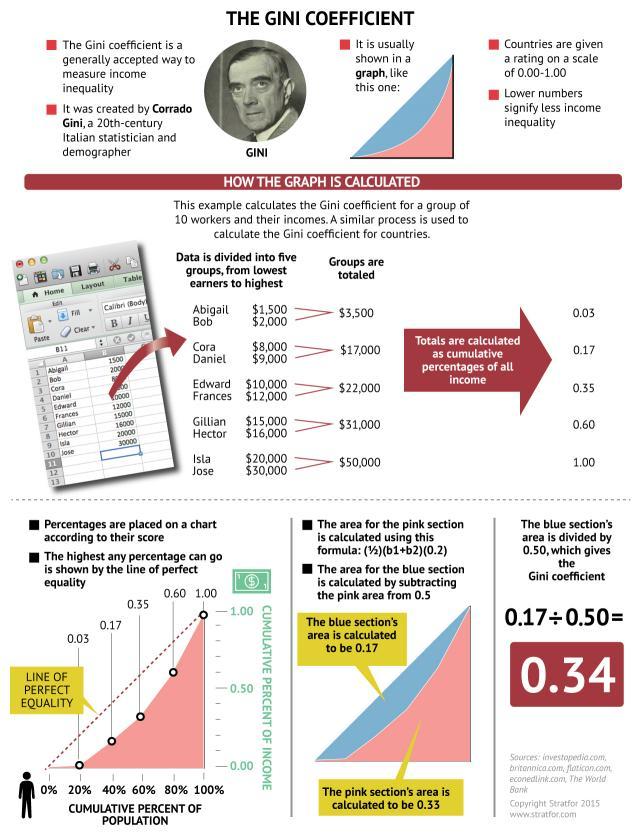

It was hard to be sure whether the members of the audience were enthusiastic because they thought Piketty was forecasting the collapse of Western democratic economies or because they thought his words applied equally well to their own society. After all, China could almost be the poster child for the process Piketty described. When Mao Zedong died in 1976, post-tax and -transfer income inequality stood at 0.31 on the Gini index. (The Gini coefficient runs from 0, meaning everyone in a country has the same income, to 1, meaning one person earns all the country’s income and everyone else earns nothing.) By 2009, China’s income inequality score had soared to 0.47, where it stubbornly remains after peaking at 0.51 in 2003. Though Chinese tax returns are too opaque to make reliable calculations regarding wealth inequality, or the uneven distribution of assets as opposed to income, he is almost certainly correct that this figure has risen even faster than the country’s income inequality.

Σχετικές αναρτήσεις:

- Lynn Parramore: Interview with Joseph Stiglitz: “Economics Has to Come to Terms with Wealth and Income Inequality“, Institute for New Economic Thinking, 16 Δεκεμβρίου.

- Cingano, F. (2014) “Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth“, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No.163, OECD Publishing, 09 Δεκεμβρίου.

- PEW Research, Global Attitudes Project: Middle Easterners See Religious and Ethnic Hatred as Top Global Threat–Europeans and Americans Focus on Inequality as Greatest Danger, 16 Οκτωβρίου.