Hugh, E., (2013), “As good as it gets in Latvia?”, Fistfulofeuros Blog, 29 September.

“This raises a final question, which, while not central to the issues of this paper, is nevertheless intriguing: How can a country with a low minimum wage, weak unions, limited unemployment insurance and employment protection, have such a high natural rate [of unemployment]?”

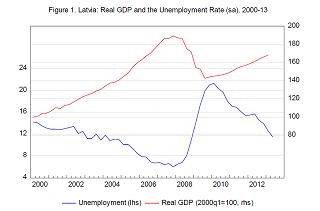

“To summarize, the actual unemployment rate is still probably higher than, but close to the natural rate of unemployment. Latvia may well want to take measures to reduce its natural rate, but the recovery from the slump is largely complete.”

“Boom, Bust, Recovery Forensics of the Latvia Crisis”, Olivier Blanchard, Mark Griffiths and Bertrand Gruss

With these words three IMF economists (hereafter BGG) effectively signed off on their study of “what just happened on Latvia” and, they hoped, drew to a close a debate which has been going on now for some 6 years. In fact, far from closing the debate, what they may have done is effectively extend it into new terrain, since these apparently harmlesss words – “the recovery from the slump is largely complete” – have far reaching implications, as does the methodology they use for reaching it. These implications reach well beyond Latvia, and even far beyond the Baltics and the CEE in general, despite the conclusion that everyone seems to be reaching that Latvia was just a “one off”. Possibly without intending to do so, they have drawn onto the clinical investigation table issues which have been mounting up in the theoretical lumber rooms of neoclassical growth theory for some time now, issues which begin to assume a paramount practical importance in the context of our rapidly ageing societies. What, for example, do we understand by the term “convergence” these days? And if “steady state” growth can no longer be understood as implying a constant growth rate (trend growth in developed economies is now systematically falling) should we be considering the possibility that headline GDP growth will at some point turn negative, even if GDP per capita may continue to rise, due to the fact that populations are steadily starting to shrink. And if the answer to the former question is “yes”, then what are the implications of this for the financial system, for the system of saving and borrowing, and for the sustainability of legacy debt? Not little questions these, but ones which will need to find answers and responses in countries like Latvia over the next couple of decades.

Relevant Posts

- Blanchard, O., Griffiths, M. and Gruss, B., (2013), “Boom, Bust, Recovery: Forensics of the Latvia Crisis”, Final Conference Draft, Fall 2013 Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, 19-20 September.

- European Commission, (2013), “Member States’ Competitiveness Performance and Implementation of EU Industrial Policy report 2013”, European Commission, 25 September.