World Employment and Social Outlook – Trends 2015 (full report), International Labour Organization, Ιανουάριος 2015.

Summary

Renewed turbulence over the employment horizon

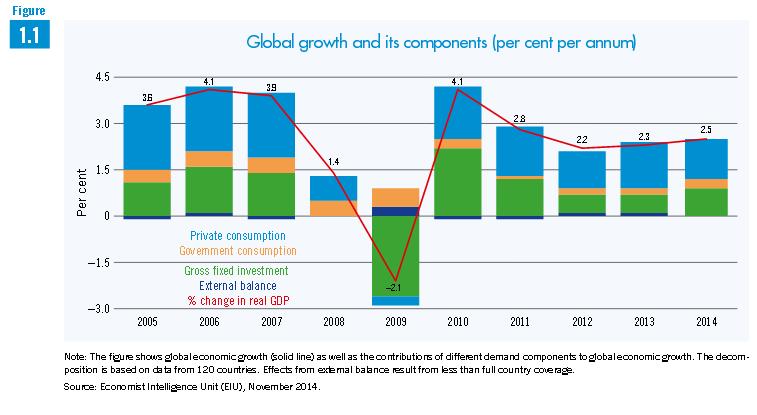

The world economy continues to expand at rates well below the trends that preceded the advent of the global crisis in 2008 and is unable to close the significant employment and social gaps that have emerged. The challenge of bringing unemployment and underemployment back to pre-crisis levels now appears as daunting a task as ever, with considerable societal and economic risks associated with this situation.

The global employment gap caused by the crisis continues to widen

This report finds that the global employment outlook will deteriorate in the coming five years. Over 201 million were unemployed in 2014 around the world, over 31 million more than before the start of the global crisis. And, global unemployment is expected to increase by 3 million in 2015 and by a further 8 million in the following four years.

The global employment gap, which measures the number of jobs lost since the start of the crisis, currently stands at 61 million. If new labour market entrants over the next five years are taken into account, an additional 280 million jobs need to be created by 2019 to close the global employment gap caused by the crisis.

Youth, especially young women, continue to be disproportionately affected by unemployment. Almost 74 million young people (aged 15–24) were looking for work in 2014. The youth unemployment rate is practically three times higher than is the case for their adult counterparts. The heightened youth unemployment situation is common to all regions and is occurring despite the trend improvement in educational attainment, thereby fuelling social discontent.

The employment situation is improving in some advanced economies, while remaining difficult in much of Europe…

There is a reversal across regions in the employment outlook. Job recovery is proceeding in advanced economies taken as a group – though with significant differences between countries. Unemployment is falling, sometimes retrieving pre-crisis rates, in Japan, the United States of America and some European countries. In southern Europe, unemployment is receding slowly, though from overly high rates.

… and is deteriorating in emerging and developing economies

By contrast, after a period of better performance compared to the global average, the situation is deteriorating in a number of middle-income and developing regions and economies, such as Latin

America and the Caribbean, China, the Russian Federation and a number of Arab countries. The employment situation has not improved much in sub-Saharan Africa, despite better economic growth performance until recently. In most of these countries, underemployment and informal employment are expected to remain stubbornly high over the next five years.

The significant fall in oil prices that has continued in early 2015 will, if sustained, improve employment prospects somewhat in importing countries. However, this is unlikely to offset the impacts of a still fragile and uneven recovery – one that will worsen for oil exporters.

As a consequence, the improvements in vulnerable employment have stalled in emerging and developing countries. The incidence of vulnerable employment is projected to remain broadly constant at around 45 per cent of total employment over the next two years, in stark contrast to the declines observed during the pre-crisis period. The number of workers in vulnerable employment has increased by 27 million since 2012, and currently stands at 1.44 billion worldwide. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia account for more than half of the world’s vulnerable employment, with three out of four workers in these regions in vulnerable employment.

Likewise, progress in reducing working poverty has slowed. At the end of this decade, still one out of 14 workers is expected to live in extreme poverty conditions.

Income inequalities have widened, delaying global economic and job recovery

On average, in the countries for which data are available, the richest 10 per cent earn 30–40 per cent of total income. By contrast, the poorest 10 per cent earn around 2 per cent of total income.

In several advanced economies, where inequalities historically have been much lower than in developing countries, income inequalities have worsened rapidly in the aftermath of the crisis and in some instance are approaching levels observed in some emerging economies. In emerging and developing economies, where overall inequalities have typically fallen, levels remain high and the pace of improvement has slowed considerably.

Underpinning some of these developments is the decline in medium-skilled routine jobs in recent years. This has occurred in parallel to rising demand for jobs at both the lower and upper ends of the skills ladder. As a result, relatively educated workers that used to undertake these medium-skilled jobs are now increasingly forced to compete for lower-skilled occupations. These occupational changes have shaped employment patterns and have also contributed to the widening of income inequality recorded over the past two decades.

Rising inequalities have also undermined trust in government, with a few exceptions. Confidence in government has been declining particularly rapidly in countries in the Middle East and North Africa region, but also in the advanced economies, East Asia and Latin America.

Falls of such magnitude, in particular if they accompany stagnant or declining incomes, can contribute to social unrest. The report estimates that social unrest has gradually increased as joblessness persists. Social unrest tended to decline before the global crisis and has increased since then. Countries facing high or rapidly rising youth unemployment are especially vulnerable to social unrest.

The employment and social outlook can be boosted

This turbulent picture can be changed provided that the main underlying weaknesses are tackled. As highlighted in previous ILO analysis, aggregate demand and enterprise investment need to be bolstered, including through well-designed employment, incomes’, enterprise and social policies. Credit systems should be reoriented to support the real economy, notably small enterprises. The weakness in the Euro area needs to be addressed with conviction. And, mounting inequalities must be addressed through carefully designed labour market and tax policy.

There is also scope for addressing the persistent social vulnerabilities associated with a fragile job recovery, notably high youth unemployment, long-term unemployment and labour market exit, particularly among women. This means carrying out inclusive labour market reforms so as to support participation, promote job quality and update skills.

Σχετικές αναρτήσεις:

- Carrera, S., Guild, E. & Eisele, K. (2014) “Rethinking the Attractiveness of EU Labour Immigration Policies: Comparative perspectives on the EU, the US, Canada and beyond“, Justice and Home Affairs, CEPS Paperbacks, 13 Νοεμβρίου.

- Barslund, M. & Busse, M. (2014) “Making the Most of EU Labour Mobility“, Social welfare policies, CEPS Task Force Reports, 07 Οκτωβρίου.

- Beblavý, Μ., Maselli, Ι. & Veselkova, Μ. (2014) “Let’s get to Work! The Future of Labour in Europe“, Economic Policy, CEPS Paperbacks, 10 Ιουλίου.